More about receptive bilinguals

Why words don’t come when they are needed?

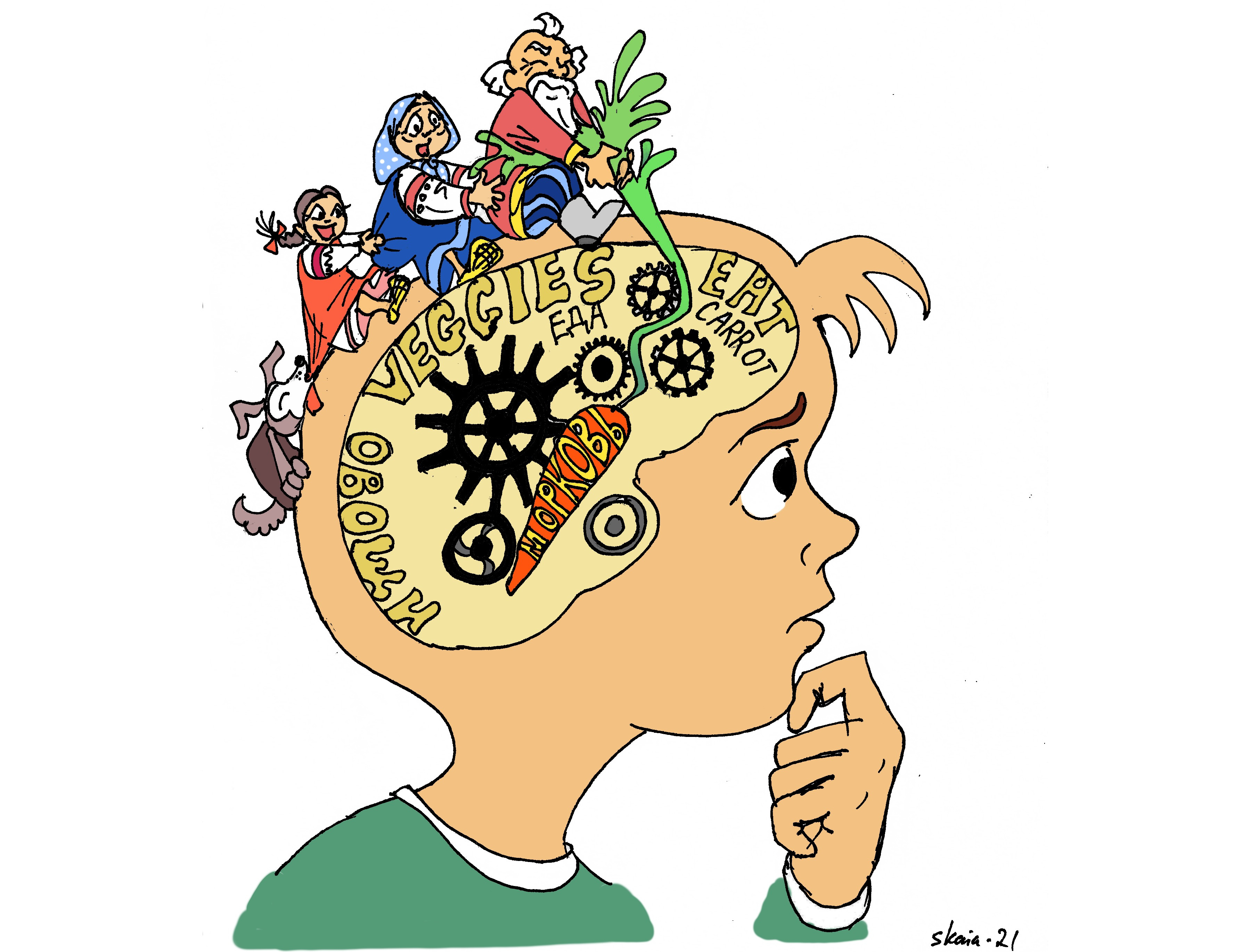

Those who “understand but don’t speak” (called receptive bilinguals) have two main problems: a small vocabulary and a shaky grammar knowledge (as I said in the post about my Ph.D. thesis). This post is about vocabulary (and grammar will be discussed in the next post).

First, receptive bilinguals, as shown by studies (my own and my colleagues’ ones), always have very low proficiency in the language that they only understand, and they simply don’t know many words. Typically, they know words for something discussed at home all the time: words for family members (the equivalents of “mom”, “dad”, “sister”, “brother”), for things they usually do (“eat”, “sleep”, “homework”, “sick”), food, clothes, things in the home. There is even a term for this: “kitchen language”. One step away from home-related topics – and they literally have no words.

But even with the words they do know, things are far from simple.

“I understand what people are saying, but when I try to say something myself, words run away,” one adult receptive bilingual told me.

I saw this effect many times with some of my school-age students in our Russian program who understand Russian to some extent but usually reply to their parents in English. (I teach Russian in Canada to children of Russian-speaking parents). I show the student a picture, for example, with several vegetables, and ask in Russian, “Show me a carrot”. The student shows a carrot, without any problems. Then we talk about other pictures. After a couple of minutes, I point at the same carrot and ask, “What is it?” And the student cannot answer. The student tries and tries to recall the word, and then says, “I don’t know”. I say the beginning of the word. Sometimes it helps, sometimes it doesn’t. And when I say the whole word, the student says, “I knew it!”

That’s why linguists distinguish active and passive vocabulary. Active vocabulary contains words that a person says. Passive vocabulary contains words that this person understands but does not say. Even monolinguals’ passive vocabulary is slightly bigger than active. People may understand but never say certain very formal words, or dialect words. But the worse a person knows a language, and/or the less frequently uses it, the larger the difference. Receptive bilinguals’ active vocabulary is much smaller than their passive one.

Why this difference? Because the child doesn’t use the heritage language frequently enough.

In psycholinguistics, two interesting effects are known, both related to the frequency of use of a given word. The first one is related to it directly, and is called the Word Frequency Effect. The more often we encounter a word (hear, read, say or write it), the faster we fish it out of our memory when we need to understand it or say it. In everyday life, the difference between frequent and rare words is not so noticeable, because it can be just a few milliseconds. But in language studies (for example, when one names an object in a picture, or reads a word), where reaction time is measured to a millisecond, the difference is clearly seen.

And when a bilingual person speaks one of the languages very rarely, all the words of that language behave like rare words. That is, it takes long to recall them.

The second effect can be seen specifically with rare words. It is called the Tip-of-the-Tongue Effect: the person knows the word, but cannot say it, because they cannot remember what it sounds like. The person can describe what the word means, can reject other people’s wrong guesses, and sometimes can even say something about its form: that it’s long (or short), or what letter it starts with. Everyone had this experience at least a few times. But receptive bilinguals get into this state very often, maybe even every couple of words.

That’s why receptive bilinguals often cannot recall the word they need, and so they switch to the language in which they are more comfortable. And the less they speak their receptive language, the lower the frequency of use of all its words, and the deeper they “sink” in the memory. And the harder it is to pull them out. The harder it is to pull them out, the less they speak this language… It becomes a vicious circle.

What can be done to help a child receptive bilingual with this? Teach words. And the child needs to say them. How to teach? It’s not an easy question. Heritage language teachers around the world create various methods. Though our area, heritage language teaching, is relatively new, we can make use of many second language teaching methods, methods used by speech-language pathologists, and native language teaching methods. But this post is not about methods, it’s about things we need to know when choosing methods for a given child.

Marina Sherkina-Lieber, Ph.D.

Illustration by Sofia Kanibolotskaia

RESEARCH

receptive bilinguals vocabulary understanding speaking